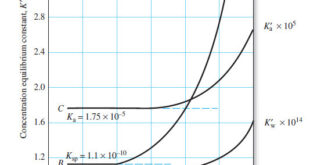

The Effect of Electrolyte on Chemical Equilibria – Experimentally, we find that the position of most solution equilibria depends on the electrolyte concentration of the medium, even when the added electrolyte contains no ion in common with those participating in the equilibrium. – For example, consider again the oxidation of …

Read More »What is Analytical Chemistry?

What is Analytical Chemistry? Analytical chemistry is what analytical chemists do. – Analytical chemistry is too broad and active a discipline for us to easily or completely define in an introductory textbook. Instead, we will try to say a little about what analytical chemistry is, as well as a little …

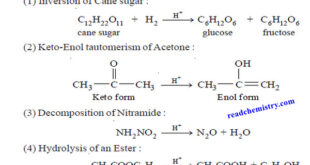

Read More »Acid-Base catalysis (definition – Examples – Mechanism)

– In this topic, we will discuss Acid-Base catalysis: definition, Examples and Mechanism. Acid-Base catalysis – A number of homogeneous catalytic reactions are known which are catalysed by acids or bases, or both acids and bases. These are often referred to as Acid-Base catalysts. – Arrhenius pointed out that acid …

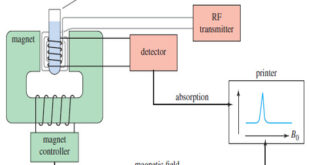

Read More »NMR spectrometer

What happens in an NMR spectrometer? – Before discussing the design of spectrometers, let’s review what happens in an NMR spectrometer. – Protons (in the sample compound) are placed in a magnetic field, where they align either with the field or against it. – While still in the magnetic field, …

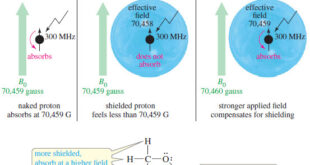

Read More »Magnetic Shielding by Electrons

– In this topic, we will discuss the Magnetic Shielding by Electrons Magnetic Shielding by Electrons – Up to now, we have considered the resonance of a naked proton in a magnetic field, but real protons in organic compounds are not naked. – They are surrounded by electrons that partially …

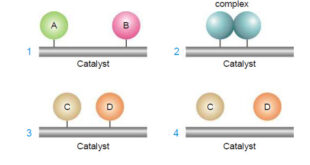

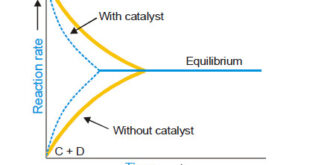

Read More »Theories of catalysis

Theories of Catalysis – There are two main theories of catalysis: (1) Intermediate Compound Formation theory. (2) The Adsorption theory. – In general, the Intermediate Compound Formation theory applies to homogeneous catalytic reactions and the Adsorption theory applies to heterogeneous catalytic reactions. The Intermediate Compound Formation Theory – The Intermediate …

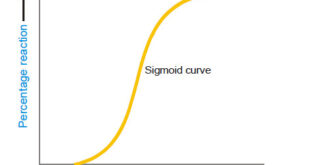

Read More »Autocatalysis, Catalytic poisoning and Negative Catalysis

– In this topic, we will discuss Autocatalysis, Catalytic poisoning and Negative Catalysis. Catalytic poisoning – Very often a heterogeneous catalyst in rendered ineffective by the presence of small amounts of impurities in the reactants. – A substance which destroys the activity of the catalyst to accelerate a reaction, is …

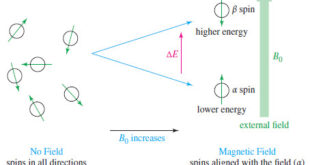

Read More »NMR – Theory of Magnetic Nuclear Resonance

Introduction to NMR – Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) is the most powerful tool available for organic structure determination. – Like infrared spectroscopy, NMR can be used with a very small sample, and it does not harm the sample. – The NMR spectrum provides a great deal of information about …

Read More »Characteristics of Catalytic Reactions

– In this topic, we will discuss general Characteristics of Catalytic Reactions and Promoters. General Characteristics of Catalytic Reactions – Although there are different types of catalytic reactions, the following features or characteristics are common to most of them. (1) A catalyst remains unchanged in mass and chemical composition at …

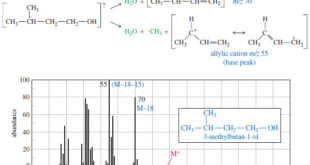

Read More »Fragmentation Patterns in Mass Spectrometry

– In this topic, we will discuss the Fragmentation Patterns in Mass Spectrometry. Fragmentation Patterns in Mass Spectrometry – In addition to the molecular formula, the mass spectrum provides structural information. – An electron with a typical energy of 70 eV (6740 kJ mol or 1610 kcal mol) has far …

Read More »Catalysis: Types of Catalysis

– In this topic, we will discuss the Catalysis and The types of catalysis : Homogeneous catalysis – Heterogenous catalysis. What is Catalysis? – Berzelius (1836) realised that there are substances which increase the rate of a reaction without themselves being consumed. – He believed that the function of such …

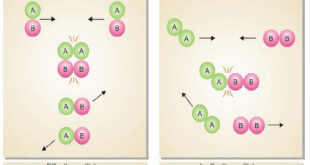

Read More »Collision theory of Reaction rates

Collision theory of Reaction rates – According to collision theory, a chemical reaction takes place only by collisions between the reacting molecules. However, not all collisions are effective. – Only a small fraction of the collisions produce a reaction. – The two main conditions for a collision between the reacting …

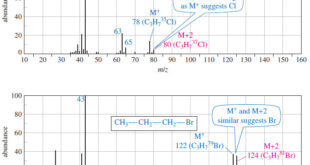

Read More »Determination of the Molecular Formula by Mass Spectrometry

Determination of the Molecular Formula by Mass Spectrometry – we can Determine the Molecular Formula by Mass Spectrometry and we will discuss : (A) High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (B) Use of Heavier Isotope Peaks (A) High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry – Although mass spectra usually show the particle masses rounded to the nearest …

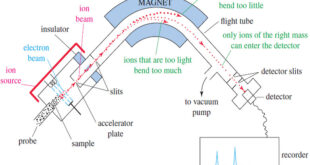

Read More »Mass Spectrometry : Introduction

Mass spectrometry (MS) provides the molecular weight and valuable information about the molecular formula, using a very small sample. Introduction to Mass Spectrometry – Infrared spectroscopy gives information about the functional groups in a molecule, but it tells little about the size of the molecule or what heteroatoms are present. …

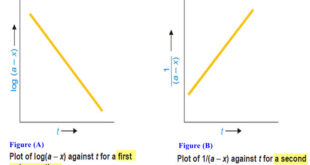

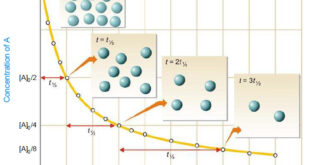

Read More »How to determine the order of reaction?

Determination of the order of reaction – There are at least four different methods to determine the order of reaction as follows: Using integrated rate equations Graphical method Using half-life period The Differential method Ostwald’s Isolation method (1) Using integrated rate equations – The reaction under study is performed by …

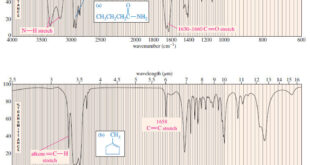

Read More »Characteristic Absorptions of Carbonyl Compounds

– In this subject, we will talk about Characteristic Absorptions of Carbonyl Compounds such as Ketones, Aldehydes, Amines, and Acids. Characteristic Absorptions of Carbonyl Compounds – Because it has a large dipole moment, the C=O double bond produces intense infrared stretching absorptions. – Carbonyl groups absorb at frequencies around 1700 …

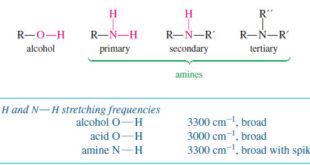

Read More »Characteristic Absorptions of Alcohols and Amines

– In this topic, we will discuss the Characteristic Absorptions of Alcohols and Amines by examples. Characteristic Absorptions of Alcohols and Amines – The O-H bonds of alcohols and the N-H bonds of amines are strong and stiff. – The vibration frequencies of O-H and N-H bonds therefore occur at …

Read More »Second order reaction

Second order reaction – Let us take a second order reaction of the type 2A ⎯⎯→ products – Suppose the initial concentration of A is a moles liter–1. – If after time t, x moles of A have reacted, the concentration of A is (a – x). – We know …

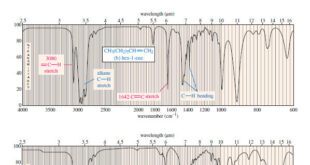

Read More »Hydrocarbons: Infrared Spectroscopy of Hydrocarbons

Infrared Spectroscopy of Hydrocarbons – Hydrocarbons contain only carbon–carbon bonds and carbon–hydrogen bonds. – An infrared spectrum does not provide enough information to identify a structure conclusively (unless an authentic spectrum is available to compare “fingerprints”), but the absorptions of the carbon-carbon and carbon-hydrogen bonds can indicate the presence of …

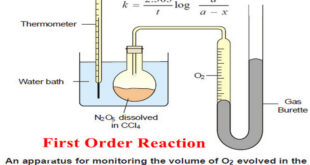

Read More »First Order Reaction -Examples and Solved problems

First order reaction – Let us consider a first order reaction: A → products – Suppose that at the beginning of the reaction (t = 0), the concentration of A is a moles liter–1. – If after time t, x moles of A have changed, the concentration of A is …

Read More » Read Chemistry

Read Chemistry